Quick Turns

The Beauty of A Poem's Shifts featuring a poem by Todd Dillard and a prompt

Driving in the first snowfall of the year, someone slammed on their brakes in front of me to make a sudden turn. Luckily, I have lived in the land of snow all my life and could stop in time, but a less experienced driver may have slid or struggled to stop without a collision. This sort of quick turn can be dangerous, pointing out the need for attention, for reaction, for being present.

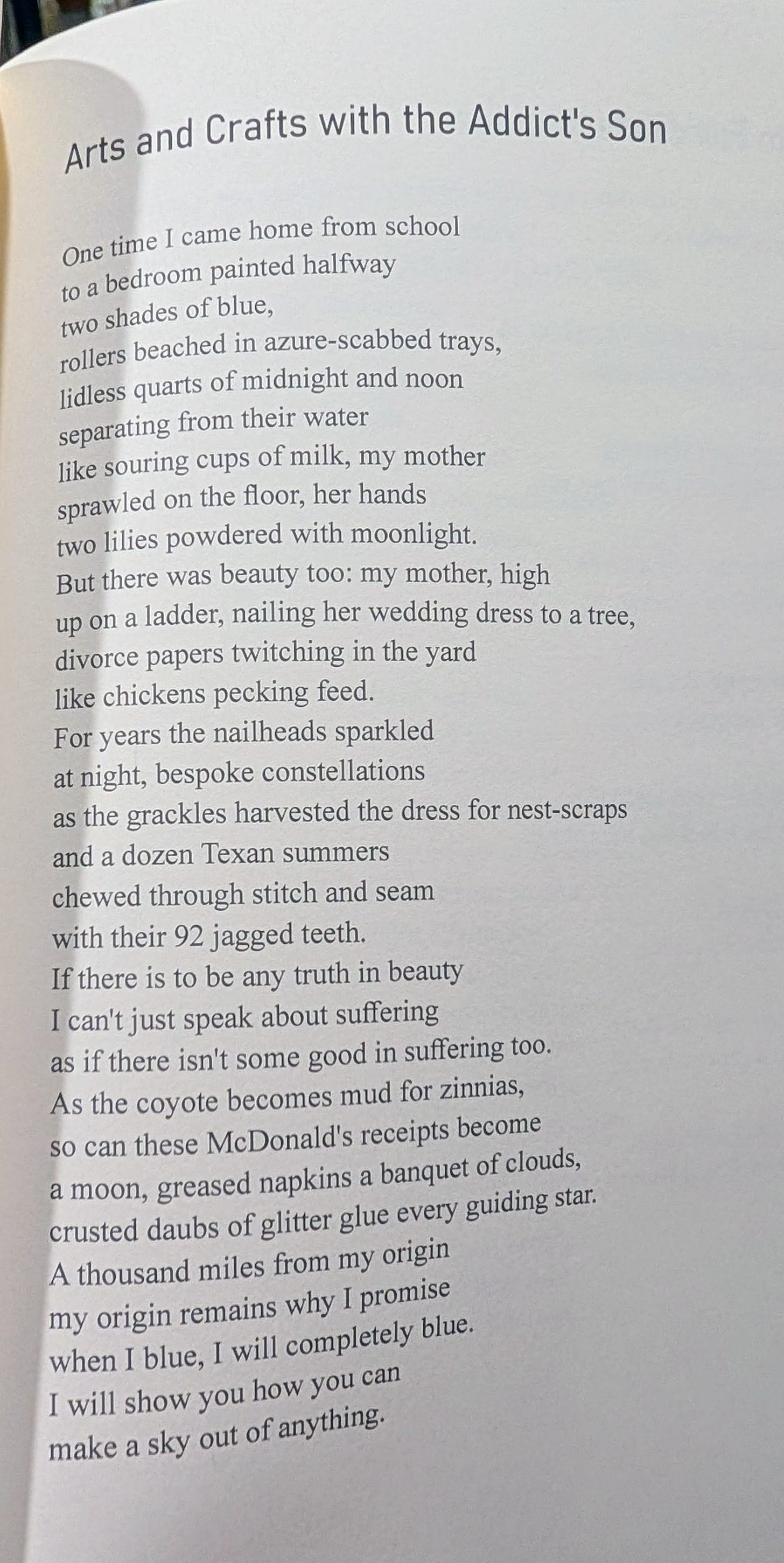

BUT…I love quick turns in poems, unexpected shifts in content or image that create tension, build layers, and sometimes lead to emotional outcomes the reader may not have expected. A poem I’ve read recently whose turns have stayed with me is “Arts and Crafts with the Addict’s Son” by Todd Dillard from his most recent chapbook Ragnorak at the Father/Daughter Dance from Variant Lit. Read the poem below, and then I’ll talk through my thinking about the turns.

The poem begins with a narrative from childhood, the speaker coming home to find a mother sprawled in the midst of a half-painted room. Images of daylight/midnight and two colors of blue, like sky, like an ocean, even the rollers “beached” in the trays. Dillard doesn’t need to explain the opening image, as the title does that work. The poem then turns on a “but” to say “there was beauty, too.”

The first image of the poem, though bursting with lush language and color, is not a beautiful memory. The “but” turns us to a different memory of the mother nailing her wedding dress to a tree, letting us in on the secret that life with the mother wasn’t always difficult. In this second anecdote, the poem shifts in time as well as content. The dress is destroyed over time by grackles and weather, yet the nails continue to sparkle. The language in this section uses the vernacular of sewing as its central focus—bespoke, stitch, seam, teeth which makes another title connection, completely disparate from the first one.

At this point in the poem, the two stories, though different in tone, diction, and purpose, are building a multidimensional portrait. Both scenes deal with creation—painting, fabric—and link the reader back to the title. But where will the poem go from here? The reader might expect another anecdote that relates to art or craft, another facet of the mother.

Instead Dillard switches to the poem’s first abstraction with the assertion about beauty and suffering, an abstraction he has earned with the stories above, and one that is illuminated below it with two more shifts.

The first is to a coyote who becomes mud for the zinnias, an image of life cycles, how one thing becomes another. The speaker as son becomes a parent in the rest of the poem, so although the coyote image is an outlier, it serves as a bridge between the abstraction and the emotional content that follows.

The second shift is not only in subject but in space and time. In the context of this chapbook of poems that explores the father/daughter releationship, the jump to the McDonalds reciepts, greasy napkins, and glitter glue moves the reader forward in time to the speaker’s present as a parent in a place a thousand miles away from where the first two scenes take place.

When Dillard makes his final turn back to the initial narrative of the poem while also remaining anchored in the present, the reader is punched in the gut by the promise of a father to be different kind of parent, to “completely blue,” a concept we feel so deeply due to the first images in the poem. I so admire Dillard’s ability to use turns in his poems to create both disjunction and investment in the reader. I am almost always surprised by something in Todd’s poems and never in a bad way.

Reading a Todd Dillard poem requires attention, reaction, being present. Just like driving in the snow, though much more pleasant of a ride. I highly recommend you check out his work for yourself.

PROMPT:

Using Dillard’s structure as a road map, try to write your own poem that follows this skeletal formula: anecdote, anecdote, abstraction, bridge image, time leap, emotional resonance. (It’s not as easy as I’m making it sound…)

Also using Todd’s poem as a prompt, start a poem with a memory from childhood that is less than happy and write toward a more current situation, tying them together through color and image.